The bleak outlook for government bond returns

Key points

• Despite fears about high levels of public debt, government bond yields in developed countries remain low on the back of low inflation, low short-term interest rates, low levels of private sector borrowing, banks buying bonds rather than lending, and strong investor flows into bond funds.

• While these factors may constrain government bond yields in the short term, yields are likely to rise over the medium term resulting in capital losses for investors as higher short- term interest rates are factored in, private sector borrowing recovers, and investors demand a risk premium for high public debt levels.

• Government bond yields in the US, Europe and Japan are well below fair value. Australian bonds with their relatively high yields are close to fair value.

Introduction

There is a distinct cloud hanging over the return outlook for government bonds in many advanced countries. Government bonds were the star performer in 2008 when economic growth collapsed, central banks slashed short-term interest rates and investors rushed into bonds as a safe haven, thereby pushing down their yields and resulting in capital gains for investors. Looking forward, their outlook is clouded by low starting point yields, the prospect that short-term interest rates will start to rise, and the risk that when private sector borrowing picks up the competition between the public and private sectors for funds will result in rising bond yields. While a US double dip back into recession may help sovereign bonds, it can be just as easily argued a looming fiscal crisis at some point down the track is a much bigger threat if investors lose patience with the pace of improvement in budget deficits.

Low yields

Sovereign bond yields were pushed sharply lower through the dark times of the global financial crisis. While bond yields have risen from their lows they still remain relatively low in the US, Europe and Japan, despite all the concerns about high budget deficits and sovereign debt. The still low level of bond yields reflects a range of factors:

• Inflation is low with core inflation rates still falling in most developed countries.

• Short-term rates are near zero in the US, Europe and Japan and are expected to remain low for an ‘extended period’.

• Private sector borrowing is still depressed, so the public sector has little competition for funds.

• Banks in the US and elsewhere have been buying government bonds (borrowing from central banks at near zero interest rates and investing in higher yielding government bonds to rebuild their balance sheets).

• US mutual fund data shows US retail investors have been piling into bond funds. Last year a record US$390 billion flowed into bond mutual funds, whereas US equity mutual funds saw a modest outflow. Bond fund inflows have remained strong so far this year. Quite clearly, investors are still very cautious of shares, preferring the yield (albeit low) on offer from bonds.

.bmp)

• Finally, while bond yields have been pushed up in countries perceived to have excessive public debt levels and a perceived greater risk of default – Greece being the prime example – core advanced countries may have actually benefited from a flight to safety.

For the immediate future we don’t see a big change: inflation is likely to remain low in advanced countries reflecting high levels of unemployment and very low capacity utilisation rates, the start of interest rate hikes in the US, Europe and Japan is still some way off and private sector borrowing will take a while to recover.

.bmp)

Low level bear market in government bonds

However, short of an extended outbreak of deflation, on a medium to longer-term basis, it is hard to be optimistic on the outlook for government bond returns in advanced countries for the following reasons:

• Starting point yields are very low suggesting that even if yields are unchanged at current levels returns will be low.

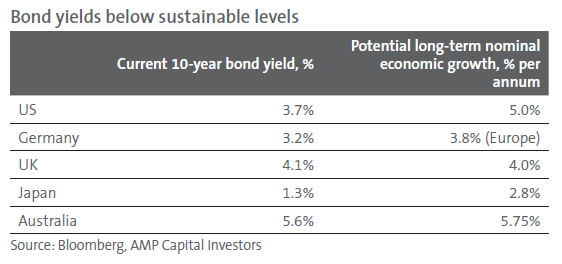

• Bond yields in the US, Europe and Japan are arguably below the levels that can be justified on a long-term basis. Over the long-term, there is a rough relationship between bond yields and long-term nominal economic growth (inflation plus real economic growth). The following table looks at current 10-year bond yields relative to our assessment of their long-term value based on their potential nominal gross domestic product (GDP) growth. While those in the UK and Australia are around fair value, those in the US, Germany and Japan are well below.

• Sometime in the next six to nine months investors will start to factor in higher short-term interest rates in key advanced countries and this will likely see longer-term bond yields pushed upwards.

• As the global recovery gathers pace, private sector borrowing will rise. If budget deficits are not reduced substantially this will result in an increase in competition for funds and hence higher bond yields. This will be magnified if banks regain confidence in lending to the private sector and cut their investment in government bonds at the same time.

• When confidence is regained in the sustainability of the economic recovery in advanced countries, it is likely investors will start to switch away from bonds into shares. Given the amount of money that has flowed into US bond funds over the last year this is a real risk factor for US bond yields. The big question is when will confidence in the sustainability of the economic recovery in the US take a turn for the better? The key is likely to be employment. Many super bears have hung their view on poor employment, hence arguing the US recovery won’t be sustainable once the impact of government stimulus ends. However, a range of indicators are now suggesting US employment will start rising again sometime in the next few months: unemployment claims are down sharply, layoffs have collapsed, job advertisements are on the rise and various business surveys point to a upswing in hiring plans. While US payroll employment fell by 36,000 persons in February, this appears to be due to the impact of severe snowstorms. Were it not for this, employment looks likely to have been positive, pointing to strong employment gains in March. So if employment starts to turn positive in the next few months, as appears probable, then confidence in the US recovery becoming self sustaining will likely improve dramatically. This should see funds flowing from bonds back into stocks and bond markets starting to factor in higher cash rates.

• Finally, if it looks like governments will be too slow in reducing budget deficit levels in countries with high debt levels (which includes most advanced countries, except Australia) then investors will start to demand a higher risk premium. Particularly with the impact of aging populations looming, this is likely to make it even harder to reduce budget deficits.

While some fret that China may tire of funding US budget deficits, this doesn’t seem likely anytime soon given the interest China has in supporting its exports. But of course, if they do then this would be another source of upwards pressure on government bond yields. The bottom line is that government bonds offer poor return prospects going forward. Look out for a low level bear market in government bonds.

Implications

There are several implications to all of this for bond investors. First, government bonds in the US, Europe and Japan offer poor medium-term return prospects as yields will likely rise. Australian government bonds look more attractive given their higher yields and low sovereign risk. Second, emerging market government bonds are arguably also more attractive reflecting much lower levels of public debt and the prospect they will see sovereign credit ratings increased relative to those in advanced countries.

.bmp)

Finally, corporate debt or credit is more attractive than public sector debt as default rates top out, gearing has been cut, and yield spreads to public debt narrow further.

Dr Shane Oliver

Head of Investment Strategy and Chief Economist

AMP Capital Investors