Australian house prices – overvalued but undersupplied

Key points

- Australian housing remains very expensive, but undersupply continues to be an issue. Worsening affordability is likely to constrain average house price growth to around 5% over the year ahead.

- Expensive housing and high household debt levels are a risk. However, in the absence of higher unemployment, much higher interest rates or a big supply increase, a US-style collapse in Australian house prices is unlikely.

Introduction

The Australian housing market has been heating up again. The question is, can it continue? The outlook for house prices is very important for Australians and the Australian economy, given that housing is the biggest investment most families undertake. Poor affordability has significant social consequences and the unwinding of high house prices in the US shows the economic damage it can cause.

Australian house prices on the rise again

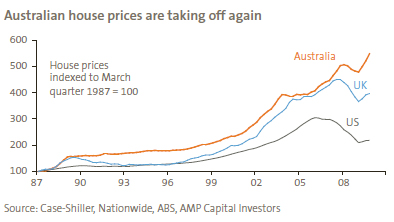

Australian house prices rose 13.6% last year and this strength appears to have continued into this year. House prices in Australia have performed far better than those in the UK and US over the last few years, largely due to the stronger performance of the Australian economy. Australian house prices are even stronger than China’s house prices, which were up 10.7% over the last year. So where to from here?

Australian housing is expensive and overvalued

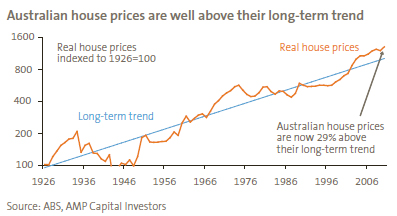

Australian housing is very expensive on most measures. Australian house prices are well above their long-term trend. The trend rate of growth in real house prices over the last 80 years has been 3% per annum, which is consistent with long-term real gross domestic product growth. However, since the mid-1990s house prices have risen well above trend and remain there.

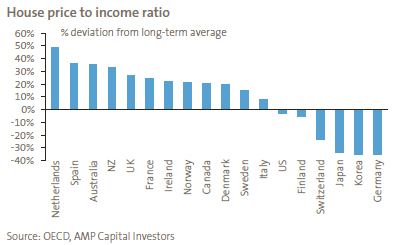

It is possible to rationalise the strength in house prices over the last 15 years on the grounds that house price to income ratios have been pushed up by the growth of two income families, lower interest rates and financial deregulation. These factors have arguably increased the amount of money people can borrow and hence pay for a house. However, this rationalising fails to explain why Australian house prices are so high on international comparisons, given these considerations also apply in other countries.

According to the 2010 Demographia International Housing Affordability Survey, Australian housing trades on a median multiple of house prices to annual household income of 6.8 times, compared to 5.1 times in the UK and 2.9 times in the US. According to 2009 data from the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD), the ratio of Australian house prices to incomes is about 35% above its long-term average, which puts it at the top end of comparable countries.

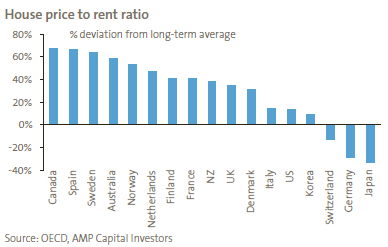

House prices are high relative to rents. According to the OECD, the ratio of house prices to rents in Australia is 58% above its long-term average. This is well above most other comparable countries. The OECD data suggests a gross rental yield of just 3.5% on houses and 4.5% on units. This is well below the 7% plus net rental yield available on directly held commercial property.

The rise in house price to income ratios over the last 20 years has gone hand in hand with a large rise in household debt. In 1990, the ratio of household debt to annual household disposable income in Australia was less than 40% and at the low end of OECD countries. This ratio is now 155% and at the high end of OECD countries. Naturally, this has led some to fret that the Australian housing market is a giant bubble at risk of collapsing at some point.

Is housing supply an issue in Australia?

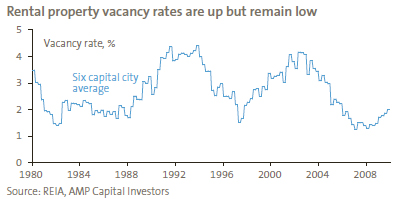

There are a number of positives underpinning the Australian housing market. The big positive for Australian house prices is a major undersupply of housing. The last few years has seen the supply of dwellings lag underlying demand, reflecting a surge in demand and the global financial crisis. Cumulative underbuilding over the last few years probably stands at around 120,000 dwellings. Australia will likely start about 165,000 dwellings this year. However, underlying demand will be around 200,000. This undersupply is reflected in continuing low vacancy rates in rental housing. Underbuilding contrasts with the massive housing oversupply that arose during the US housing boom.

It is also worth noting that the Australian housing market didn’t see the same deterioration in lending standards that occurred in other countries. Homeownership rates haven’t increased. In fact, they have fallen for the typical first home buyer age group. Most of the increase in mortgage debt over the last few decades went to older and wealthier Australians, and this is reflected in a relatively low mortgage arrears rate despite the debt increase.

These factors are helping to support Australian house prices, despite the fact they are relatively expensive.

Outlook

The intersection of high house prices with high household debt levels leaves Australia vulnerable. However, in the absence of a big surge in the supply of dwellings or a serious threat to the ability of Australians to service their loans (either through much higher unemployment or interest rates), a sharp fall in house prices is unlikely. In fact, none of these seem likely any time soon.

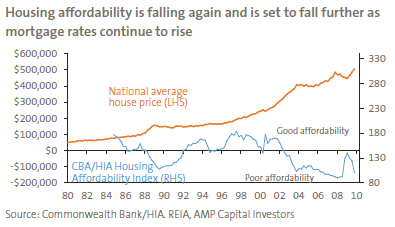

In terms of the year ahead, strong auction clearance rates but softening housing finance presents a mixed picture. Further gains in average house prices are likely as employment is rising. Also, although interest rates are on the way up, they are still well below previous highs. For example, the standard variable rate is currently averaging around 6.9%, compared to the 2008 peak of 9.6%. However, the ending of the first home owners boost and the renewed deterioration in housing affordability suggest gains will be constrained. Affordability improved into mid-2009, mainly due to a 40% collapse in mortgage rates. With house prices now back at record levels and mortgage rates on the rise again, affordability is pushing back to previous lows and likely to weaken further.

Our assessment remains that average house price gains will slow to around 5% over the year ahead. Middle to upper end housing could be a bit stronger, given this type of housing is less sensitive to mortgage rates and will clearly benefit from higher employment and rising overall wealth levels. Low end housing could see prices soften, given a greater sensitivity to mortgage rate increases, the ending of the first home owners boost and weakness in first home buyer demand.

Concluding comments

High house prices and high household debt levels remain Australia’s Achilles heel. A renewed deterioration in affordability is also a big negative. However, given constrained supply, low levels of mortgage stress and the improving economy, the most likely outcome is for constrained gains over the year ahead.

Dr Shane Oliver

Head of Investment Strategy and Chief Economist

AMP Capital Investors

Important note: While every care has been taken in the preparation of this document, AMP Capital Investors Limited (ABN 59 001 777 591) (AFSL 232497) makes no representation or warranty as to the accuracy or completeness of any statement in it including, without limitation, any forecasts. Past performance is not a reliable indicator of future performance. This document has been prepared for the purpose of providing general information, without taking account of any particular investor’s objectives, financial situation or needs. An investor should, before making any investment decisions, consider the appropriateness of the information in this document, and seek professional advice, having regard to the investor’s objectives, financial situation and needs. This document is solely for the use of the party to whom it is provided.