The Australian dollar breaking higher

Key points

- The Australian dollar (A$) appears to be resuming its rising trend. While the US dollar (US$) picture has become more mixed, the combination of strong commodity prices, a rising interest rate differential in Australia’s favour and relatively strong public sector debt fundamentals are likely to push the A$ much higher. We remain of the view the A$ will reach parity against the US$ this year.

- A stronger A$ presents ongoing challenges for the Australian economy as trade-exposed manufacturers and service industries suffer a loss of competitiveness. For investors, it means there is a case to limit exposure to unhedged international investments.

Introduction

It seems whenever economists start talking about parity for the A$ against the US$, the A$ loses puff and heads lower. Right now, it seems to be heading in the direction of parity again and, despite the chips having gone stale and the champagne flat from the last aborted parity party, we remain of the view it will get there some time this year. While the US$ outlook is no longer the clear positive for the A$ that it was last year, a widening interest rate differential in Australia’s favour, strong commodity prices and favourable perceptions of Australia’s economic fundamentals certainly are.

US$ picture is mixed, but doesn’t preclude A$ strength

Through much of the last decade, the US$ has been in a broad downtrend and this made it easier for the A$ to push higher. However, since late 2009 there have been increasing signs the US$ may have bottomed against major currencies. While the US is still beset by an excessive level of both private and public debt and needs a lower currency if it is to rebalance its economy in favour of higher exports, Europe and Japan are arguably in worse shape. The fiscal crisis in southern European countries and the associated negative impact on economic growth in the region is likely to ensure the European Central Bank will have to maintain easy monetary policies longer than the US Federal Reserve (Fed). This augurs poorly for the euro over the next year or so. Ongoing deflation will maintain pressure on the Bank of Japan to retain easy money much longer than the Fed, which augurs poorly for the yen.

Against this, the likely resumption of Chinese Renminbi appreciation in the near term and tightening monetary conditions in many emerging countries point to downwards pressure on the US$ against emerging market currencies. Also, commodity currencies are being supported by earlier moves to monetary tightening and strong commodity prices. In this context, it’s worth noting the strength in oil prices, amongst other things, has pushed the Canadian dollar (CAD) above parity against the US$.

The point is, whereas the US$ may have reached some sort of bottom against the yen and the euro, it doesn’t preclude further strength in the A$. In this regard, it is noteworthy the A$ has held up well against the US$ since late last year – essentially going sideways – despite the euro falling around 12% in value against the US$. Essentially, there are three major factors pushing the A$ up: strong commodity prices, a widening interest rate differential, and strong economic fundamentals.

Commodity prices are strong and likely to trend higher

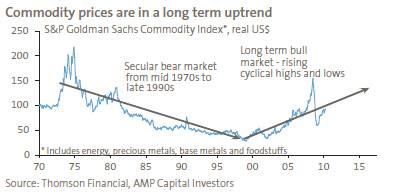

The trend in commodity prices is likely to remain up as Chinese economic growth remains strong, the US housing cycle bottoms and infrastructure spending globally remains high, all at a time when commodity supply remains constrained. Our view is that commodity prices have now embarked on another cyclical upswing in the context of a long term bull market, or super cycle (refer to chart below). This is positive for the A$ as commodities make up 60-70% of Australia’s exports.

The interest rate differential in Australia’s favour is likely to widen further

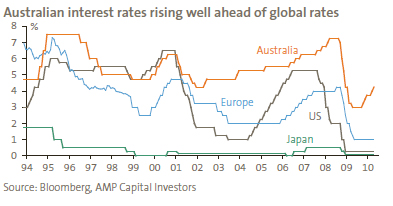

At 4.25%, Australian interest rates are well above those in the US, Europe and Japan where the range is 0-1%. What’s more, the Reserve Bank of Australia (RBA) has signalled more rate hikes ahead. However, the message from the Fed is rate hikes are still some time away and rate hikes in Europe and Japan are still over the horizon. As a result, the interest rate differential in favour of Australia is set to widen. By year-end, the short-term interest rate differential is likely to have increased to 4.25% versus the US, 4.00% versus Europe and 4.75% versus Japan.

Strong economic fundamentals

The global financial crisis (GFC) has likely dramatically improved investor perceptions of Australia. It’s the only Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development country not to have succumbed to recession through the GFC, it has zero net public debt, and is seen as well managed and a relatively safe way to invest in the strong China story. This favourable shift in perceptions is likely adding to long term upwards pressure on the A$.

So how far can the A$ go?

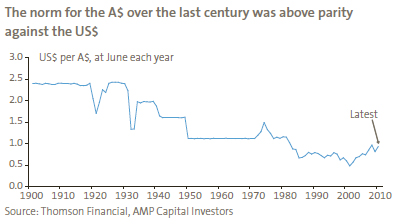

During the post-float period since 1983, the general perception was that fair value for the A$ was around US$0.70 cents and most fair value models for the A$ constructed over this period confirmed this (as would be expected). However, it’s likely this relatively narrow period of history misses the longer term perspective and the changed reality facing Australia. Back in 1901, the equivalent of A$1.00 bought US$2.40 and for most of the last century the A$ was above parity against the US$. The long term slide in the A$ between 1901 and 2001 reflected a combination of soft commodity prices, which adversely impacted Australia’s terms of trade, and a perception of Australia as a mediocre, inflation-prone ‘old’ economy (refer to chart below).

These drivers have now all turned around. Commodity prices are in a long term upswing and Australia is seen as well managed with inflation under control and interest rates that are relatively high, in part reflecting a potentially higher return on capital. In fact, back in the early 1950s when Australia’s terms of trade (the ratio of export prices to import prices) was around current high levels, A$1.00 actually bought US$1.12. In short, it is likely the sub-parity period from the 1980s was the aberration for the A$ and the improvement in Australia’s relative fundamentals suggest it is likely the A$ is going back above parity against the US$. This level is likely to be tested some time this year.

Impact of rising A$ on the economy and shares

From an economic perspective, the strength in the A$ is a mixed bag. To the extent that it’s a positive sign regarding the global growth outlook and will reduce the cost of imported goods to Australia and hence inflation, it’s good news. It’s particularly good news for Australian consumers, as imports comprise about 30% of consumption goods, meaning consumers will see lower prices than otherwise would have been the case for fuel, cars, clothing and many electrical goods. As such, a strong A$ will help the RBA in controlling inflation and may mean interest rates have to rise by less than would otherwise be the case.

A stronger A$ is bad news for companies with exposure to trade or with earnings sourced offshore. It’s much easier to identify companies that will lose from a rising A$ via the impact on their earnings, e.g. resources, multi-national industrials and building material shares, than to identify companies that benefit because of lower import costs, e.g. retailers and airlines. With 30% or so of listed company earnings sourced overseas, each 10% rise in the A$ will mechanically cut earnings by about 3%. Strength in the A$ is worse for large cap shares (which have greater foreign exposure) than for small caps (which often benefit from cheaper imports).

It’s worth stressing, though, that while there are negatives for trade-exposed companies, to the extent that a strong A$ is a sign of stronger economic growth overall, it’s more positive than negative. In fact, in recent times a strong A$ has gone hand-in-hand with economic strength, e.g. from 2003-07, and a weak A$ has correlated with economic weakness, such as in the second half of 2008.

From a longer term perspective, the rise in the A$ will present challenges for the economy. It’s effectively helping to shift economic resources to the strongly growing resources sector of the economy, which is fine from a technical economic perspective but such restructuring will have social consequences for many people.

The strong A$ and investors

For investors, the rise in the value of the A$ may not be good news as it will reduce the value of offshore investments, unless they are hedged. Global bond and property funds are usually hedged back to Australian dollars to remove the currency impact. However, global share funds are usually unhedged, because the A$ normally moves in line with share markets and so tends to smooth out their volatility. In 2008, the fall in the value of the A$ helped cushion the fall in international share markets for Australian-based investors in unhedged international shares; though in 2009 the rise in the value of the A$ completely offset the recovery in global share markets.

Fully-hedged international share funds are available. With the A$ likely to see further gains as the global recovery continues, there is a case to remain in, or consider investing in, hedged international share funds as opposed to unhedged funds.

Concluding comments

The broad trend for the A$ is likely to remain up amid strong commodity prices, a widening interest rate differential in Australia’s favour and favourable economic fundamentals. In fact, the A$ is likely to follow the CAD up to parity against the US$.

Dr Shane Oliver

Head of Investment Strategy and Chief Economist

AMP Capital Investors